-

25 Apr

#67 – European Responses to China’s Belt & Road Initiative

event #67, Thursday, May 3rd, 2018

SPEAKERS

Romano PRODI

President of the European Commission (1999-2005); Prime Minister of Italy (1996-1998; 2006-2008)WANG Jianye 王建业

Professor and Dean, Guangzhou Institute of International Finance; Former Managing Director, Silk Road Fund (2015-2018)

ABSTRACT

One year ago, ThinkIN China invited Romano Prodi, former President of the European Commission and former Italian Prime Minister, to speak on the future of Europe after Brexit – the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union. Being widely viewed as a huge step back in Europe’s integration process, this unexpected event gave rise to numerous questions on the challenges for the EU, that went along with it. Brexit constitutes a symptom of a general EU malaise. Euroscepticism and populist movements are on the rise because EU citizens don’t perceive the European Union to address their concerns. The absence of unity and political coordination is moreover undermining the EU’s role on the international stage as well as its efficiency in responding to new challenges and opportunities, such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative, to whom the EU has not defined a unified policy yet. Southern and Eastern European countries are more open to Chinese investments compared to the leading European economies, which are concerned about an influential role of China in their internal affairs. Indeed, most of Chinese investments have landed in Germany, France, and Italy which are also the countries that are willing to create an EU-wide investment screening mechanism to control foreign investments in Europe as wells as to protect crucial industrial sectors and infrastructures. However, Portugal, Greece, and Cyprus, as well as some Eastern European countries, are not in favor of this initiative. While preparations for the China-EU summit in July 2018 are already well underway, the internal debate on how to adequately respond to the BRI is still going on within the EU.

In the upcoming ThinkIN China event, Romano Prodi and Wang Jianye, dean of Guangzhou Institute of International Finance and former executive director of the Silk Road Fund, will discuss the challenges and opportunities that the Belt and Road Initiative has brought to Europe and shed light on the various responses that European countries are giving to the most intriguing and ambitious geopolitical initiative of the XXI century.

RSVP

In order to RSVP send your name & affiliation to events@thinkinchina.asia. Please note that there’s a limited number of seats, therefore successful confirmation of registration will be sent according on a first-come-first-served basis.

Time: 18.00 – Registration commences; 18.50 – Registration closes

Venue: The Bridge Cafe

Location: Rm 8, Bldg 12, Chengfu lu, Beijing 北京市海淀区成府路五道口华清嘉园12号楼8号

Price: FREEConditions

- An ID must be shown upon arrival

- Registration will start at 18.00

- Guests will not be allowed to enter after the registration closes at 18.45

- In order to speed up security procedures at the entrance, large items are not recommended to be carried

Related Posts

- 10000

- 10000

WANG Jianye 王建业 Professor and Dean, Guangzhou Institute of International Finance Rotating Secretary General, International Working Group on Export Credits Professor Wang is the former Managing Director of the Silk Road Fund (2015 - Feb 2018), Economic Counselor and Chief Economist of the Export-Import Bank of China (2008-2013).…

WANG Jianye 王建业 Professor and Dean, Guangzhou Institute of International Finance Rotating Secretary General, International Working Group on Export Credits Professor Wang is the former Managing Director of the Silk Road Fund (2015 - Feb 2018), Economic Counselor and Chief Economist of the Export-Import Bank of China (2008-2013).… - 60

SPEAKERS Romano PRODI, President of the European Commission (1999-2005); Prime Minister of Italy (1996-1998; 2006-2008) WANG Jianye 王建业,Professor and Dean, Guangzhou Institute of International Finance; Former Managing Director, Silk Road Fund (2015-2018) One year ago, for our event#60, ThinkIN China invited Professor Romano Prodi, former President of the European…

SPEAKERS Romano PRODI, President of the European Commission (1999-2005); Prime Minister of Italy (1996-1998; 2006-2008) WANG Jianye 王建业,Professor and Dean, Guangzhou Institute of International Finance; Former Managing Director, Silk Road Fund (2015-2018) One year ago, for our event#60, ThinkIN China invited Professor Romano Prodi, former President of the European…

Read more... -

24 Apr

WANG Jianye

WANG Jianye 王建业

Professor and Dean, Guangzhou Institute of International Finance

Rotating Secretary General, International Working Group on Export Credits

Professor Wang is the former Managing Director of the Silk Road Fund (2015 – Feb 2018), Economic Counselor and Chief Economist of the Export-Import Bank of China (2008-2013). He is a Professor and Director of the Volatility Institute at NYU Shanghai, and Adjunct Professor at Peking University. Prior to joining China Exim Bank, he held various positions at the International Monetary Fund (1989-2008), where he led IMF policy surveillance and lending missions to member countries. Prof. Wang holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Columbia University (1989) and B.A. from Peking University (1983). His recent publications include Debt, Currency and Related Reforms (China Financial Publishing House, 2012).

Read more... -

17 Apr

#66 Event Report – Can China Shape Global Modernity?

SPEAKER

LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China

On March 23rd ThinkIN China inaugurated the new spring season with Professor Liang Xuecun from Renmin University of China. As an expert in IR, following a PhD in nationalism of contemporary China at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and post-doctoral studies at the University of St Andrews and King’s College London, during the event she investigated one of the most debated issues within the scenario of international relations: can China shape global modernity and support a development that promotes cooperation with the rest of the world?

Towards the essence of Chineseness: understanding the concepts of modernity, identity and nation

In order to answer these questions, Liang pointed out the importance of these three terms: modernity, identity and nation, stressing their controversy and complexity.

What is modernity? Not all the scholars perceive this word in the same sense. It is not only referred to the present meaning, but also to the emergence of rationality, of a market-industrial economy, of a bureaucratically organized state and of a political creed of popular rule. Charles Taylor perceived modernity as “a wave, flowing over and engulfing one traditional culture after another”. But if it is a process in constant evolution, is it right to consider the existence of only one type of modernity? Liang stressed that the meaning of modernization is often perceived by many Chinese people as a process of westernization, since the concept is a Western creation, that aims at changing a country according to Western values.

The concept of identity is difficult to define, too. According to Anthony Giddens, in the post-traditional order identity is not inherited or static, but it becomes an endeavor that we continuously work and reflect on. It’s not a set of observable characteristics of a moment, but becomes an account of a long process. As the identity of each individual is not only the result of heritage, but also of social interactions and experiences, also contemporary China is not only a reflection of the past, but also a process of continuous changes which are subject to external influences.

Liang also introduced the complexity of defining what a nation is. Many scholars since 1882 have contributed to explore the meanings of this concept. Among them, Charles Tilly analyzed state-making and nation formation interdependently, but he soon realized that nation “remains one of the most puzzling items in the political lexicon”. Liang stressed that the concepts of nation and nationalism are difficult to be articulated especially in China, since they are not the results of home-grown processes in traditional Chinese politics. Before the Chinese empire collapsed at the beginning of the twentieth century, different ethnic groups had coexisted under the same Tianxia (天下, which is literally translated into “all under the heaven”, in ancient China denoted the land, space and area divinely appointed to the Emperor by universal principles of order, but is today associated with political sovereignty), but managed to keep their own customs and dialects. When the modern Chinese state was founded, it tried to join the international club of nation-states by reconfiguring its political structure on the basis of rather fragmented imperial legacies. This is an onerous task.

China is a multinational state which largely inherited the imperial territory of the past. Since nation refers to a distinct, homogenous group of people united by common history, culture, language and territory, the concept is totally foreign to ancient Chinese tradition. For example, during Tang dynasty (618-907AD) the society was very multiethnic, not only Persians, Indians, Koreans and Vietnamese held positions of high-rank officials, but also the Emperor Taizong (reigned 629-649 AC) married a Xianbei (proto-Mongol) wife.

Since the concept was not native to the Chinese tradition, it became an arduous task to decide where the boundaries between Chinese people, state and nation should be drawn and how to operate as a single nation in political practices despite the very complex composition of 56 ethnicities.

Zhonghua minzu (中华民族) and the principle of sovereignty

The term Zhonghua minzu (Chinese nation) was first coined by the late Qing political thinker Liang Qichao in 1902. Initially it only referred to the Han ethnicity but it was then expanded to include the Five Races Under One Only Union (Wuzu Gonghe 五族共和), one of the most important principles upon which the Republic of China was founded in 1911. It referred to the five major ethnic groups in China based on the ethnic categories of the Qing: the Han (汉族),the Manchu (满族), the Mongols (蒙族), the Hui (回族) and the Tibetans (藏族).

When Sun Yat-sen seized power at the beginning of last century, he initially considered the Manchu as a group of foreign invaders to be expelled, but then he identified only the Manchu ruling class as the perpetrators to be eliminated for the purpose of nation unification. Today, the Chinese nation refers to all 56 ethnic groups living inside the borders of China.

The fact that the country faces serious challenges in terms of nation-building has led to China’s adherence to Westphalian sovereignty, since Westphalian sovereignty bases authority on the territorial state rather than on cultural identity. This is also evident by the fact that respect for sovereignty, as well as territorial integrity and national unity, remains the core Chinese national interests.

A list of twelve “core socialist values” was then showed to the audience. Among them appeared: prosperity, rule of law, democracy, patriotism and equality. How do we make of these principles, Liang asked? A plethora of good words reveal the indecisiveness in articulating a Chinese identity. And it is impossible even in principle to be harmony between all good values, according to Isaiah Berlin. Other charts showed that the percentage of Chinese citizens who believe in the necessity to defend their way of life is significantly lower than its neighboring countries. These figures underlined that the primary goal of Chinese nationalism is not to defend a “Chinese” way of life, Instead, Chinese nationalism concerns itself primarily with enhancing the country’s international status. The promotion of The Double Top University Plan in 2017 or hosting the Olympic Game as it did in 2008 are good examples to illustrate this point.

Is it therefore correct to say that China has adopted Western values?

Alastair Iain Johnson made distinctions between the process of learning and adapting. Learning involves a fundamental change of assumptions and approaches while adapting requires no more than adjusting to changing circumstances. The question is whether China has been learning or adapting.

Some scholars as James Mann argued that a big number of China observers assume economic liberalization would sooner or later lead to political liberalization. That is how engagement policy with China has been sold politically in the United States. Other decision makers like Wesley Clark considered the Chinese approach as an adapting one. Clark stressed that China was not becoming more like a typical Western country, which suggested that it had merely adapted to the external environment, but not learned from it.

Liang asked what if the primary goal of engagement policy – to transform China according to a Western blueprint – cannot be achieved? There is no doubt that China is trying to make contributions to the so-called international society, but it does so in its own way.

Referring to the public speech held by Xi Jinping at the UN Assembly in Geneva in January 2017 titled “Work Together to Build a Community with Shared Future for Mankind”, it appears reasonable to ask what are the principles on which this global community should be founded. Is it possible to build a shared future without liberal internationalism, universalism and cosmopolitanism?

If on one side China is going abroad, supporting a development which promotes cooperation through cultural plans and important infrastructural projects, on the other side it still keeps its own characteristics without being conquered and dominated as were other countries in the past. So nowadays it is difficult to determine which directions Chinese foreign policy will take and which strategies it will adopt in the future. What is sure is that a real change within the political Chinese system will not occur tomorrow, but new outlooks and features will be gained through a process which requires time.

The Q&A session gave space to a stimulating debate that expressed the expectations and at the same time the uncertainties regarding future developments in global modernity. Liang, however, showed optimism in the future, arguing that despite China may perhaps find itself in the trap of Thucydides, facing an increasing rivalry with the US, at the same time it does not intend to subvert the international order. China is more helpful to the world today and is struggling to improve its soft power. The Belt and Road Initiative was launched in response to the economic threats arising from the TTP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) and through this project China encourages new business routes and promotes economic development. Chinese government tries to enhance its image also abroad doing much effort for the overseas community: through the diaspora, China has the possibility to understand foreign countries and influence them.

At the same time, however, its engagement in Africa and the “peaceful rise discourse” leave us with a big question about China’s real strategic intentions. Can the further increasing engagement in the economic framework stay apart from security? Is China an harmonious nation or does the government use this rhetoric to justify Chinese behavior?

These questions will be answered only in the modernity that will be revealed day by day.

Report written by Alessia Bonato

Related Posts

- 10000

event #66, Friday, March 23rd, 2018 SPEAKERS Helwig SCHMIDT-GLINTZER, Founding Director, China Centrum Tübingen LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China ABSTRACT ** Professor Schmidt-Glintzer had a personal emergency and left for Germany right before the event, so the talk has seen professor Liang Xuecun taking…

event #66, Friday, March 23rd, 2018 SPEAKERS Helwig SCHMIDT-GLINTZER, Founding Director, China Centrum Tübingen LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China ABSTRACT ** Professor Schmidt-Glintzer had a personal emergency and left for Germany right before the event, so the talk has seen professor Liang Xuecun taking… - 10000

LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村 Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China Liang received her Ph.D degree from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her doctoral thesis, A Tense Time: Explaining and Understanding Contemporary Chinese Nationalism, looks to domestic socioeconomic changes and systematic pressures on the international level to explain the…

LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村 Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China Liang received her Ph.D degree from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her doctoral thesis, A Tense Time: Explaining and Understanding Contemporary Chinese Nationalism, looks to domestic socioeconomic changes and systematic pressures on the international level to explain the…

Read more... -

02 Apr

LIANG Xuecun

LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村

Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China

Liang received her Ph.D degree from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her doctoral thesis, A Tense Time: Explaining and Understanding Contemporary Chinese Nationalism, looks to domestic socioeconomic changes and systematic pressures on the international level to explain the revival of nationalism in contemporary China. During her Ph.D years, she taught a variety of undergraduate courses including Government and Politics of China, Intergovernmental Relations, Asian International Relations, and Asian Comparative Politics. After graduation, she conducted post-doctoral studies at the University of St Andrews, where she focused on nationalism and state building in late modernizers. She has then been a Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of War Studies at King’s College in London, before moving back to China and started teaching at Renmin University in Beijing.

Related Posts

- 10000

event #66, Friday, March 23rd, 2018 SPEAKERS Helwig SCHMIDT-GLINTZER, Founding Director, China Centrum Tübingen LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China ABSTRACT ** Professor Schmidt-Glintzer had a personal emergency and left for Germany right before the event, so the talk has seen professor Liang Xuecun taking…

event #66, Friday, March 23rd, 2018 SPEAKERS Helwig SCHMIDT-GLINTZER, Founding Director, China Centrum Tübingen LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China ABSTRACT ** Professor Schmidt-Glintzer had a personal emergency and left for Germany right before the event, so the talk has seen professor Liang Xuecun taking…

Read more... -

19 Mar

#66 – Can China Shape Global Modernity?

event #66, Friday, March 23rd, 2018

SPEAKERS

Helwig SCHMIDT-GLINTZER, Founding Director, China Centrum Tübingen

LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China

ABSTRACT

** Professor Schmidt-Glintzer had a personal emergency and left for Germany right before the event, so the talk has seen professor Liang Xuecun taking the lead in the explanation **

Professor Schmidt-Glintzer will talk about the predicament of China after the end of Imperial rule as a country that tries to become a member of the global community while at the same time maintaining a distinct identity. In a sense China has not yet regained an idea of itself and indeed centers around an “empty space”, such as the empty character of Tian’Anmen Square, the symbolic center of China. At the same time China shows a remarkable ability to deal with contradictions both within the country and in its relations with the neighbors.

Schmidt-Glintzer will delineate the historical identity of China as the center of All Below Heaven – 天下, as a multicultural entity that had to deal with migration, with centrifugal and centripetal forces, as well as extensive foreign exchanges for centuries. The core question is whether or not China could be a model for modernization and ordering of the world in a harmonious way.

Related Posts

- 10000

LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村 Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China Liang received her Ph.D degree from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her doctoral thesis, A Tense Time: Explaining and Understanding Contemporary Chinese Nationalism, looks to domestic socioeconomic changes and systematic pressures on the international level to explain the…

LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村 Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China Liang received her Ph.D degree from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her doctoral thesis, A Tense Time: Explaining and Understanding Contemporary Chinese Nationalism, looks to domestic socioeconomic changes and systematic pressures on the international level to explain the… - 10000

SPEAKER LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China On March 23rd ThinkIN China inaugurated the new spring season with Professor Liang Xuecun from Renmin University of China. As an expert in IR, following a PhD in nationalism of contemporary China at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and…

SPEAKER LIANG Xuecun 梁雪村, Assistant Professor, Renmin University of China On March 23rd ThinkIN China inaugurated the new spring season with Professor Liang Xuecun from Renmin University of China. As an expert in IR, following a PhD in nationalism of contemporary China at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and…

Read more... -

22 Feb

#65 – Event Report – Philanthropy in China: New Era, New Challenges, New Strategies

SPEAKERS

HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation

ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center

ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation

For the last event of the Fall Season 2017, ThinkIN China gathered for the second time in the co-working and event venue 3ESPACE, key project of the SANY Foundation, to discuss about philanthropy and charity in the new era of China. For the occasion we invited three speakers, differently committed to non-profit and charity initiatives in China: HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director of the China Association for NGO Cooperation; ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director of the Child Development Center within the China Development Research Center; ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer of the Sany Foundation.

Dr. Huang Haoming drove our attention to two crucial dimensions which need to be addressed in order to get a realistic idea of how philanthropic and charitable projects developed throughout the years up to present. He indeed focused first on the complex legal and political evolution of NGOs’ status in China, both home-based and overseas, specifically pointing out the relevance of the recent improvements triggered by the 2016 new Charity Law. Secondly, he delved more deeply into the future prospects for further developments of philanthropy in China, not only in terms of effective implementation of the newly released norms, but also taking into consideration which new issues Chinese NGOs will be dealing with at the global level.

After briefly outlining the differences between social organizations, social service agencies (private non-enterprise unions) and foundations, Dr. Haoming provided detailed data about the outstanding growth of the so called ‘society organizations’ in China, most notably of foundations. These in fact recorded the quickest and most significant development over the last eight years, doubling in number and collecting 62.5 billions yuan out of the 78 billions totally arranged through social donations in 2016.

Charitable and non-profit organizations active in mainland China have been also facing significant changes since the new Charity Law was released in 2016, marking a big step-forward if compared to the 1999 Welfare Donations Law.

Far from only regulating donations of private fundings, assets or shares stocks, the brand-new normative covers a wider range of issues, like volunteer work, involvement of companies in charity trusts, legal recognition of organizations under the new law or the employment of the Internet and online social platforms for raising funds.

What is more, the landscape of NGOs in China has been radically transformed by the huge increase of overseas organizations which have been setting up their activities in the country. As recent as November 2017, 280 representative offices of foreign non-profit organizations were already registered, mainly in Beijing, followed by Shanghai and Guangdong province.

Remarkably, the new, clearer regulatory framework has been creating a favorable domestic environment for Chinese NGOs to expand, what has got them to adopt a more and more global approach. Their participation in international organizations and major summits, like the Hamburg G20 or the 2017 UNFCCC in Bonn, has been scaling up steadily, along with their presence in humanitarian assistance actions and public welfare projects.

Such outcomes certainly lay the groundwork for positive forecasts over future improvements, taking into account unprecedented dynamics such as a stronger focus on the rule of law, a renewed governmental support in terms of public policies and the increasing diversity of actors involved in charity projects for tackling complex and intertwined social issues.

Yet, several challenges need to be addressed in order to fully get the opportunities emerging in China’s charity sector, both at national and global level.

First of all, Chinese non-profit organizations still lack capacity resources and prepared professionals, two elements that jeopardize the overall efficiency of the activities they carry on.

A second critical point is represented by the controversial relationship between social agents and governmental authorities, since the first are in need for public resources but are also subjected to a stricter control and supervision by the latter.

The Chinese government has indeed changed its role in philanthropy fields, directly committing to increase the level of professionalism but also designing management and assessment mechanisms to make NGOs fully comply with governmental regulations.

Obstacles have emerged in fund-raising and social mobilization as well, since philanthropists and foundations still have to develop strategies for benefiting more from online platforms and channels.

Overseas NGOs active in China will also have to deal with several operational issues, such as building efficient win-win partnerships with local organizations, recruiting professional personnel through the use of China’s social security system, and improving the coordination of their often separated units, in order to actually respond to social communities’ demands.

Chinese citizens’ new awareness and interest in philanthropy and charity have been also strengthening public claims for increased transparency, accountability and legitimacy of all the actors involved.

In the next ten years, China’s social organizations are expected to enlarge their participation within the global governance system, as well as the trans-regional cooperation with their foreign peers.

Beijing has been exerting an always more prominent role in setting the international agenda as far as major global issues are concerned, from environmental and climate change policies to poverty reduction.

Such a leading position, though, requires to find a new and more effective balance between governmental policies and supervision, talents, private funds and social trust, in order to solve social problems.

How can, for instance, innovative industries contribute to reform philanthropy, enhancing professionalism and flexibility among an increasing number of stakeholders?

Higher transparency in the organizations boards and decision making process, accountability in terms of operational efficiency and financial effectivity, standardization and equality of rules for all NGOs, shared responsibility in supervising the collection and allocation of donations, they have now turned into priorities for making philanthropy and charity in China true allies in serving people’s social needs.

Zhao Chen focused more on the charity initiatives promoted by the China Development Research Foundation, initiated by the Development Research Centre of the PRC’s State Council (DRC).

Governmental background and backing to the CDRF are based on recognition that China’s outstanding rate of growth has also triggered conflicting effects, particularly in terms of social injustice and inequalities. Therefore CDRF’s mission shoulder to shoulder with the government is to keep promoting economic development while making good governance and public policies sort out social imbalances.

The foundation firstly constitutes a channel of easier communication, that is it facilitates companies and organizations to gather and get in touch with ministries and State Council’s departments active in fields where crucial social issues need to be addressed. The China Development Forum organized on annual basis is the most noteworthy example.

Secondly, the foundation is active in the government-entrusted research area, in cooperation with different ministries, through the issue of reports aimed at analyzing first class social issues and possible solutions in a wide range of sectors, from environment to education and public health.

Lastly, the CDRF directly manages development programs, mainly in the rural and poorest counties of China, like Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou provinces, which are realized as ‘social experiments’ and pilot projects. Main purpose is to collect information and achieve positive outcomes which are likely to be broadly implemented at the national level.

Since the CDRF is a non-profit organization, its mutual relation with central and local governments is necessary in order to get access to resources while making public authorities more and more accountable, as far as social welfare services are concerned.

Such strict compliance to the government directions is mirrored by the CDRF’s function of policy advocacy, which is intended to assure an efficient allocation of resources, as well as to design, release and implement accurate policies to tackle social problems identified in CDRF’s reports.

As a consequence, the foundation also exerts the role of evaluation centre once public norms are issued, specifically guaranteeing standardization in the implementation degree among difference provinces and thus contributing to continue improvements.

In the recent years, the foundation has been focusing on the education and nutrition areas, with the launching of different pilot initiatives in the most indigent parts of mainland China.

In 2009 in Ledu, Chengdu province, so called ‘MaMa Schools’ were first set off, providing pupils’ mothers training to healthy nutrition for their children.

A number of other projects then followed, offering education and concrete support to families of children at different ages.

The China Reach Parenting Program constitutes in home-visitings, in order to get in touch with parents of zero to 3-year-old babies, and inform them about accurate diets. For children between 3 and 6 years old, the foundation supported the establishment of pre-school education programs, like the Village Early Education Centers (VEECs).

With the aim of providing life course intervention on education and nutrition, the pilot project also included e-learning activities in rural primary schools for 6 to 13 years old students, and secondary vocational training to rural students until they turned 18.

The first social experiments led to national nutrition improvement plans for rural students during compulsory education, currently covering up to 834 counties and more than 34 million students.

The CDRF keeps carrying on its activities of reporting major social issues, supervising public policies and supporting collection and sharing of data, in order to promote poverty eradication from intergenerational transmission and the construction of a multidimensional social security system for the weakest sections of China’s society.

Last but not least, Zhang Shantong, Project Officer at Sany Foundation, outlined the association’s mission of promoting a scientific, transparent and professional philosophy to charity in China. Such approach is reflected in the ‘ecosystem’ offered by the 3ESPACE as an Easy, Enjoyable and Effective (3 Es) co-working space for exchanging ideas.

In the first place, the accurate and objective method the Sany Foundation has been making a point of results in a strong focus on concrete and systematic evaluations of charity projects in terms of employed resources, impact, achieved outcomes and actors which need to be involved (like NGOs and private companies).

Philanthropy and charity are able to represent real assets in tackling social issues and fostering social development when programs are designed in such way they can make the difference in the weakest and deprived categories of society.

The foundation is thus specifically committed to support pilot initiatives, like issuing high school scholarships in the form of traditional cash transfer under conditionality, in order to assess whether it could improve the students’ attendance and performances, especially in rural China.

The elaboration of such kind of projects starts with evaluating which areas (mainly rural regions) and groups (students at high school stage) are most in need of charity interventions. In such social experiments, donations and philanthropic organizations’ resources are allocated on the basis of concrete indicators, which ultimately lead to objective data – for instance the increase in academic performances of students who receive a scholarship regardless their prior grades.

Data and results are thus the key elements in the whole activity carried on by philanthropists, charitable organizations and foundations, whose contribution to China’s social development not only relies on getting access to money, but also on an always more efficient, rational and effective convergence of resources where people really need them.

Report written by Sara Paganini

Related Posts

- 10000

event #65, Monday, December 18th, 2017 SPEAKERS HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation The evolution of China’s philanthropy and non-profit space has seen…

event #65, Monday, December 18th, 2017 SPEAKERS HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation The evolution of China’s philanthropy and non-profit space has seen…

Read more... -

15 Feb

Podcast #65 – Philanthropy in China

Related Posts

- 10000

event #65, Monday, December 18th, 2017 SPEAKERS HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation The evolution of China’s philanthropy and non-profit space has seen…

event #65, Monday, December 18th, 2017 SPEAKERS HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation The evolution of China’s philanthropy and non-profit space has seen…

Read more... -

15 Feb

Podcast #64 – The Souls of China

Podcast

Related Posts

- 10000

event #64 - Tuesday, December 5th, 2017 SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After…

event #64 - Tuesday, December 5th, 2017 SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After… - 10000

SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences As we gathered for our December event at The Bridge, the theme for it was the recent…

SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences As we gathered for our December event at The Bridge, the theme for it was the recent… - 10000

Ian JOHNSON Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker IAN JOHNSON is a Pulitzer-Prize winning writer focusing on society, religion, and history. He works out of Beijing, where he also teaches undergraduate classes. Johnson has spent nearly twenty years in…

Ian JOHNSON Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker IAN JOHNSON is a Pulitzer-Prize winning writer focusing on society, religion, and history. He works out of Beijing, where he also teaches undergraduate classes. Johnson has spent nearly twenty years in… - 10000

CHEN Xia 陈霞 Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Dr. Chen Xia is a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in Beijing. She received her Ph.D in Religious Studies from Sichuan University. After graduation, she taught at Sichuan…

CHEN Xia 陈霞 Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Dr. Chen Xia is a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in Beijing. She received her Ph.D in Religious Studies from Sichuan University. After graduation, she taught at Sichuan…

Read more... -

14 Dec

#65 – Philanthropy in China: New Era, New Challenges, New Strategies

event #65, Monday, December 18th, 2017

SPEAKERS

HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation

ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center

ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation

The evolution of China’s philanthropy and non-profit space has seen a significant acceleration in recent years. The new legal blueprint, put in place with the 2016 Charity Law, is seen as an opportunity that could provide regulatory clarity, increase public trust, and move the sector forward.

Today, the proactive role of philanthropists and foundations is growing in both weight and sophistication. New technologies and the role of social media may help charitable activities in raising funds, expanding their outreach, as well as enhancing effectivity in promoting shared social goals.

At the same time, improving living standards, and the growing affluence in urban areas, are boosting awareness towards issues like poverty alleviation, healthcare, environment, and education in rural areas.

Amid these evolving trends, we want to make sense together, by asking the experts, of the milestones that shaped the sector, the current trends and, in particular, what does the future of China’s charitable sector looks like.

For this event we have partnered up with China Global Philanthropy Institute, a project supported by five Chinese and US philanthropists, committed to building a knowledge system supporting the highly development of philanthropy in China and the world.

We will be hosted for the second time this year by 3ESPACE, the flagship project of SANY Foundation, a private foundation focused on fostering Chinese education, innovation, public health, and economic development.

The after event refreshments will be provided by Bread of Life Bakery, a non-profit organization run by physically disabled young adults who have grown up in orphanages in China.

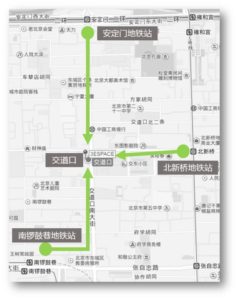

LOCATION

3ESPACE is located at the crossroad of Gulou Dongdajie and Jiaodaokou Nandajie, at the 5th floor of the Xinhua Wenhua building.

Address: 北京市东城区交道口南大街15号新华文化大厦5层

The closest subway station is Andingmen, then walk for ten minutes towards south, along Andingmen Neidajie.

Related Posts

- 10000

HUANG Haoming 黄浩明 Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation Huang became a senior engineer in 1994. Huang received his Master of Public Policy & Management from Carnegie Mellon University, USA in 1995. He is also an adjunct professor of NGO Research Center, Tsinghua University and adjunct…

HUANG Haoming 黄浩明 Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation Huang became a senior engineer in 1994. Huang received his Master of Public Policy & Management from Carnegie Mellon University, USA in 1995. He is also an adjunct professor of NGO Research Center, Tsinghua University and adjunct… - 10000

SPEAKERS HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation For the last event of the Fall Season 2017, ThinkIN China gathered for the second time…

SPEAKERS HUANG Haoming 黄浩明, Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation ZHAO Chen 赵晨, Deputy Director, Child Development Center, China Development Research Center ZHANG Shantong 章善桐, Project Officer, Sany Foundation For the last event of the Fall Season 2017, ThinkIN China gathered for the second time…

Read more... -

14 Dec

HUANG Haoming

HUANG Haoming 黄浩明

Vice-Chairman and Executive Director, China Association for NGO Cooperation

Huang became a senior engineer in 1994. Huang received his Master of Public Policy & Management from Carnegie Mellon University, USA in 1995. He is also an adjunct professor of NGO Research Center, Tsinghua University and adjunct professor of the school of public policy and management, Beijing University of Aeronautics & Astronautics. Other associate positions: member of the board of directors of Asian NGO Coalition for Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ANGOC); member of the board of directors of China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation; member of the board of directors of China Association of International Trade; member of Western Returned Scholars Association; executive member of Council of China Reform Forum and member of the China National Committee for Pacific Economic Cooperation, Human Resources Development Sub-Committee. His publications include Strategy planning for Non-profit organization (2003), Cooperation and communication between Chinese and Foreign NGOs (2001), Practice and Management for International NGOs cooperation (2000).

Read more... -

12 Dec

#64 – Event Report – The Souls of China: The Return of Religion after Mao

SPEAKERS

Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker

CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

As we gathered for our December event at The Bridge, the theme for it was the recent spiritual (re)awakening in China. From the first time Ian Johnson came to China in the 1980s until today, he noticed the changing landscape regarding how Chinese people related to temples, praying and religion in general. In the 1980s, temples in China were abandoned, destroyed, or used for different purposes. “The Souls of China”, through covering five religious groups in China, discusses the return of cultural and religious practices in the country in the 21st century. In search for moral guidance, new religious groups have been appearing. The process happened spontaneously, with people starting to donate and contribute to the rebuilding of temples.

Although the perception at first was that it was part of the relation between communism and religion, the disappearing of religious life started with the intellectual elite during the 100 years of humiliation and the movements that led to the republic. It was seen as necessary to go after the role of the political influence of religion, especially in rural villages, in order to find modernization. It continued under the Kuomintang, as some religious habits were allowed and others forbidden. Soon, communal activities of spiritual Chinese life – folk culture – became “superstition”. The Cultural Revolution was the final blow in a long process of shutting down the role of religion in China. Only in 1982, it would return to be seen as a positive cultural heritage.

The return of spiritualism that surged in China now is also part of a movement that happened around the world, as many societies saw themselves facing a “crisis of modernity”. Triggered by a feeling of spiritual vacuum (what are the ideas that hold us together as a society?) and encouraged through social media interaction, a national debate started over values and morality. The groups all unite in search of a sense of community that seemed to have been lost in many of Chinese largest cities, particularly for migrants.

Chen Xia emphasized the dramatic changes of the last twenty years, particularly in the academia – where religious studies was largely non-existent. She also emphasized how religion has helped with the transitions and transformation of Chinese society. Johnson later added how religion has been helping to explain how to respond to certain situations and guide attitudes. Later on, Chen added how Confucianism has been central to discussing heaven and behavior, but when China became a nation-state, it has been difficult to transition those habits to legislation. Thus, today and for the future of Chinese society, it is necessary also to engage Confucianism and written laws in a conversation.

The Chinese government hasn’t been ignoring this, and thus, abandoned the discourse of superstition, embracing these practices and offering subsidies to cover basic costs of religious groups. During the Q&A, Chen emphasized how the government has worked along with religious communities to create a cooperation between religion and socialism – in the hopes of building a more harmonious society.. Although concern was raised over the role of government administration and management over these religions, they are allowed to exist and practice – as long as they support the leadership of the CCP.

However, Johnson pointed out that the main concern of the people involved in these religious associations is how to both honor the past and pass it down to the next generation. It was also raised as an important point of the Chinese identity and modern discussions on this issue. Some younger Chinese attendees reaffirmed how religion was very interesting, but they didn’t feel very connected in a personal level – although didn’t consider it so far from their lives. It is part of the connection between the culture of ancient China and thus, it builds a bridge with older generations.

Report written by Julia Rosa

Related Posts

- 10000

event #64 - Tuesday, December 5th, 2017 SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After…

event #64 - Tuesday, December 5th, 2017 SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After… - 10000

Ian JOHNSON Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker IAN JOHNSON is a Pulitzer-Prize winning writer focusing on society, religion, and history. He works out of Beijing, where he also teaches undergraduate classes. Johnson has spent nearly twenty years in…

Ian JOHNSON Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker IAN JOHNSON is a Pulitzer-Prize winning writer focusing on society, religion, and history. He works out of Beijing, where he also teaches undergraduate classes. Johnson has spent nearly twenty years in… - 10000

CHEN Xia 陈霞 Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Dr. Chen Xia is a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in Beijing. She received her Ph.D in Religious Studies from Sichuan University. After graduation, she taught at Sichuan…

CHEN Xia 陈霞 Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Dr. Chen Xia is a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in Beijing. She received her Ph.D in Religious Studies from Sichuan University. After graduation, she taught at Sichuan…

Read more... -

29 Nov

#64 – The Souls of China – The Return of Religion after Mao

event #64 – Tuesday, December 5th, 2017

SPEAKERS

Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker

CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao (2017) tells the story of one of the world’s great spiritual revivals. Following a century of violent anti-religious campaigns, China is now filled with new temples, churches and mosques–as well as cults, sects and politicians trying to harness religion for their own ends. Driving this explosion of faith is uncertainty — over what it means to be Chinese, and how to live an ethical life in a country that discarded traditional morality a century ago and is still searching for new guideposts.

This book is the culmination of a six-year project following an underground Protestant church in Chengdu, pilgrims in Beijing, rural Daoist priests in Shanxi, and meditation groups in caves in the country’s south.

Along the way, Ian Johnson learned esoteric meditation techniques, visited a nonagenarian Confucian sage, and befriended government propagandists as they fashioned a remarkable embrace of traditional values. These experiences are distilled into a cycle of festivals, births, deaths, detentions, and struggle–a great awakening of faith that is shaping the soul of the world’s newest superpower.

Join ThinkIN China for a new discussion about Johnson’s recently released book, together with Dr. Chen Xia, a research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing, where she studies religions in China and Chinese philosophy.

Watch the book trailer on YouTube

Read the reviews about the book

Related Posts

- 10000

Ian JOHNSON Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker IAN JOHNSON is a Pulitzer-Prize winning writer focusing on society, religion, and history. He works out of Beijing, where he also teaches undergraduate classes. Johnson has spent nearly twenty years in…

Ian JOHNSON Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker IAN JOHNSON is a Pulitzer-Prize winning writer focusing on society, religion, and history. He works out of Beijing, where he also teaches undergraduate classes. Johnson has spent nearly twenty years in… - 10000

CHEN Xia 陈霞 Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Dr. Chen Xia is a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in Beijing. She received her Ph.D in Religious Studies from Sichuan University. After graduation, she taught at Sichuan…

CHEN Xia 陈霞 Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Dr. Chen Xia is a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in Beijing. She received her Ph.D in Religious Studies from Sichuan University. After graduation, she taught at Sichuan…

Read more... -

28 Nov

CHEN Xia

CHEN Xia 陈霞

Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

Dr. Chen Xia is a research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) in Beijing. She received her Ph.D in Religious Studies from Sichuan University. After graduation, she taught at Sichuan University for 10 years. Then she conducted a post-doctoral research in Chinese philosophy at CASS and moved to this research academy in 2003. During these years, she has been a visiting scholar at Harvard-Yenching Institute, at SOAS, and a Fulbright Visiting Scholar at Brown University. Her specialty is Religions in China and Chinese Philosophy, concentrating on Daoism.

She is the co-chief editor of Principles in the Study of Religions. This book is used widely as a text book for students in their studies of theories and methods in Religious Studies. Her book Studies of Daoist Moral Tracts focuses on Daoist ethics and moralities from Song dynasty (960-1279) till Qing dynasty (1636-1911). In recent years, she has been paying more and more attention to ecology, and is the chief editor and contributor of Studies of Daoist Ecological Thoughts. Besides doing research, she is also involved in the translation of books from Chinese to English and from English to Chinese. She is one of the translators for books like Daoism and Traditional Chinese Culture (Chinese to English), while from English to Chinese, she helped in translating Martin Luther’s Theological Thoughts, Man’s Religions and Daoism and Ecology. Her new book Introduction to Daoist Philosophy will come out in December 2017.

Related Posts

- 10000

event #64 - Tuesday, December 5th, 2017 SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After…

event #64 - Tuesday, December 5th, 2017 SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After… - 10000

SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences As we gathered for our December event at The Bridge, the theme for it was the recent…

SPEAKERS Ian JOHNSON, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker CHEN Xia 陈霞, Research Fellow, Institute of Philosophy, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences As we gathered for our December event at The Bridge, the theme for it was the recent…

Read more... -

21 Nov

Ian JOHNSON

Ian JOHNSON

Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist, writing for the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the New Yorker

IAN JOHNSON is a Pulitzer-Prize winning writer focusing on society, religion, and history. He works out of Beijing, where he also teaches undergraduate classes.

Johnson has spent nearly twenty years in the Greater China region, first as a student in Beijing from 1984 to 1985, and then in Taipei from 1986 to 1988. He later worked as a newspaper correspondent in China, from 1994 to 1996 with Baltimore’s The Sun, and from 1997 to 2001 with The Wall Street Journal, where he covered macro economics, China’s WTO accession and social issues.

In 2009, Johnson returned to China, where he writes features and essays for The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, as well as other publications, such as The New Yorker and National Geographic. He teaches undergraduates at The Beijing Center for Chinese Studies, where he also runs a fellowship program. In addition, he formally advises a variety of academic journals and think tanks on China, such as the Journal of Asian Studies, the Berlin-based think tank Merics, and New York University’s Center for Religion and Media.

He was twice nominated for the Pulitzer Prize and won in 2001 for his coverage of China. He also won two awards from the Overseas Press Club, and an award from the Society of Professional Journalists. In 2017, he won Stanford University’s Shorenstein Journalism Award for his body of work covering Asia.

In 2006-07 he spent a year as a Nieman fellow at Harvard, and later received research and writing grants from the Open Society Foundation, the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.

Johnson has published three books and contributed chapters to three others. His newest book, The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao, describes China’s religious revival and its implications for politics and society.

Learn more on his official website.

Read more... -

20 Nov

#63 Event Report – China’s Economy in the New Era

SPEAKER

Michael PETTIS, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Asia Program, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Professor of Finance, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University

The season’s second event hosted one of the most brilliant analysts of China’s economy, and financial markets in particular. Michael Pettis’ presence at The Bridge had been on the agenda for a while, and the audience was enthusiastic to hear his perspectives on the future of Chinese economic reforms after the Nineteenth Party Congress.

Pettis’ goal was to set China’s economy in context, making sense of its past growth model in order to identify future trends. In fact, according to Pettis, the Chinese case is not exceptional, thus we are able to make economic forecasts based on economic history. Pettis identified four separate phases characterizing China’s economic growth up to the present:

Deng Xiaoping’s liberalizing reforms: eliminating constraints

In the 1970s, the Chinese economy was in very serious trouble. Starting from 1978, Deng Xiaoping managed to realize China’s economic liberalization in spite of tremendous institutional constraints and elite opposition to his reforms, proving himself as ‘one of the greatest leaders of the twenty-first century.’ In fact, history has shown that such type of liberalizing reforms only occurs successfully – without causing a significant regime change – in two cases: democracies, and highly centralized autocracies such as China. In Pettis’ view, centralization of power in the 1980s paved the way for China’s growth miracle. Deng’s historic 1992 tour to southern provinces, which relaunched economic reforms after a period of stall, was precisely aimed at tackling resistance to his policies by existing elites.

Gerschenkron’s Model in China: an investment-driven miracle

Pettis argued that eliminating constraints is only the first step to realize liberalizing reforms. The second step, followed by many developing economies around the world, is the so-called investment-driven economic miracle known as the Gerschenkron’s Model, from the name of the economist Alexander Gerschenkron. In sum, developing countries tend to have low savings rates, thus some of them rely on foreign capital to fund their economic growth. However, given the significant risks associated with foreign capital, these countries have the alternative to force up savings rates in order to convert domestic savings into sufficient investments to fuel growth. The way to do this is simply to contract consumption rates by reducing households’ share of GDP, which will obviously limit their ability to spend money in the market.

According to Pettis, the fact that China has arguably the lowest households’ income share of GDP ever recorded, which corresponds to the highest savings rates in the world, cannot be explained by Chinese families’ innate preference for saving money, a popular myth about China; rather, it was caused by a precise government design that ensured indirect and systematic wealth transfers away from households and towards the government and businesses. These transfers were accomplished through a combination of currency manipulation, low wage growth relative to productivity, and negative interest rates. Subsequently, the Chinese government directed this wealth into short-term infrastructure investments. China forced savings into investments at the highest rate ever seen in history, successfully realizing an investment-driven miracle at a time when the country needed it the most.

The core of China’s structural problems: over-investment and unsustainable debt

Pettis continued by referring to the concept of ‘optimal capital level’, which implies that each country has its own level of investment – depending on a set of institutions such as legal, financial, educational, and political – determining the rate at which workers are able to use resources productively. Beyond this limit, injecting capital into the economy ceases to be productive and becomes inefficient, unless further institutional reforms are implemented.

China has passed this critical point: additional investments in unutilised infrastructure facilities, and redundant production capacity in traditional manufacturing sectors, are bringing more costs than value to the economy. Pettis identified this as the core of China’s structural problems: China invests too much, fueling an unsustainable increase in debt. In his view, every country that experienced an investment-driven boom encountered this conundrum, in parallel with the emergence of very powerful constituencies who oppose any change to the existing system. This is where China stands today at the beginning of Xi Jinping’s second mandate.

The trajectory of economic rebalancing

In order to reverse this unsustainable cycle of unproductive investment and debt, China urgently needs to switch off this engine, silencing opposition from powerful elites before it can start implementing an ambitious set of institutional liberalizing reforms. Pettis suggested two necessary steps. First, drastically re-centralizing power, after the wave of political reforms that decentralized economic policy making starting from the late 1990s. An example is the attempt to bring the extremely decentralized banking system back under the central government’s control. Second, addressing the debt problem, in its two interconnected dimensions of flow of debt and stock of debt.

The flow of debt is the mechanism that allows Chinese debt to rise at the fastest rate ever seen in history. The reason behind such rapid increase in debt is that households’ consumption is extremely low, therefore investment is misallocated towards sectors of the economy which are no longer productive: simply put, the government artificially creates demand in order to keep the manufacturing sector producing at current levels, guaranteeing employment. To reduce investment while containing unemployment, consumption must be stimulated, which requires raising households’ share of GDP at the expense of elites and local governments, the main beneficiaries of the current growth model. Unfortunately, after former Premier Wen Jiabao officially acknowledged the serious imbalances of China’s economy, the situation worsened considerably between 2007 and 2012. It is no coincidence that by the end of 2000s Chinese media began discussing the issue of vested interests: these groups became vocal as the government expressed the intention to rebalance the economy by transferring more wealth to households.

Pettis proceeded by discussing the issue of the stock of debt. China’s amount of debt is unsustainable for a developing country because it constraints growth. Pettis suggested that China assigns the cost of debt to the only economic sector which is able to pay for it: the government. Traditionally, households are secretly forced to bear the cost of debt through taxation, as happened during banking crisis in the U.S. and Europe. Indeed, China also forced households to bear the costs of the banking reform in the 2000s: unsurprisingly, consumption dropped from an already low 46 percent of GDP in the year 2000, to 35 percent in 2008. Making Chinese families pay for the debt is clearly unfeasible. Assigning this task to small and medium enterprises is also risky: Pettis noted their political vulnerability, as well as their pivotal role for future economic growth in China.

Only the government has the resources to pay for the debt: according to a recent study by Thomas Piketty et al., cited by Pettis, it has a considerable net position as a percentage of GDP, much higher than most countries: this means it can liquidate assets and use the proceeds to pay down debt and increase households’ share of GDP. Again, this implies wealth transfers from local governments to ordinary Chinese. According to Pettis, the Nineteenth Party Congress has shown political willingness to do so, but given tremendous elite opposition it is hard to predict whether these reforms will be implemented. What is sure, readjustment will come at huge costs if it is to be successful: countries that go through this process normally experience an extremely difficult transition.

In what Pettis described as the ideal rebalancing scenario, China has no choice but to revise its unfeasible GDP growth target and set it at around 2 to 3 percent, while ensuring that households’ incomes grow by 4.5 to 5 percent. In this way, local governments would pay for the debt by liquidating their assets, while growth would decelerate without causing social turmoil. According to Pettis, the government has already been trying to adopt this strategy: whether Xi Jinping has consolidated its power enough to successfully do this will only be seen when such reforms begin.

The Q&A session touched upon many interesting issues. For instance, the lack of hard budgetary constraints, which allows the government to reach virtually any GDP target by way of unprofitable bank loans to corporations and local governments: in Pettis’ view, GDP in China is not so much an ‘output’ but rather an ‘input’, decided by the government and achieved through distortions in production capacity. Another talking point concerned the ways localities can liquidate their assets: while selling real estate could make the banking system collapse, some provinces and municipalities are experimenting different strategies, such as wealth transfers to workers and pension funds. In conclusion, the political momentum seems to be there, but this does not imply that a smooth readjustment is on the horizon.

For further reference, Pettis, Michael. The Great Rebalancing: Trade, Conflict, and the Perilous Road Ahead for the World Economy. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Report written by Rebecca Arcesati

Related Posts

- 10000

- 10000

Michael PETTIS Nonresident Senior Fellow, Asia Program, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Professor of Finance, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University MICHAEL PETTIS is a nonresident senior fellow in the Carnegie Asia Program based in Beijing, where he edits China Financial Markets, a monthly analysis on income inequality, market…

Michael PETTIS Nonresident Senior Fellow, Asia Program, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Professor of Finance, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University MICHAEL PETTIS is a nonresident senior fellow in the Carnegie Asia Program based in Beijing, where he edits China Financial Markets, a monthly analysis on income inequality, market…

Read more...